Academic Writing

When Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter began designing buildings associated with the National Park Service (NPS) in the early 1900s, neither architecture nor the parks were well-known for having robust female workforces. Only thirty-nine women had graduated from four-year architecture programs in American by the turn of the century (Stratigakos, 2104), and it would be

another 20 years before the NPS hired any women as rangers. (Galper, 2016)

Whether driven by an inherent fear of predators or a practical need to protect livestock from bears, coyotes, wolves, and mountain lions, these animals and others have been in the crosshairs for hundreds of years. As far back as 1630, the Massachusetts Bay Company offered

one penny for every wolf killed. (Bacon, 2012) Today, bounties are still offered on coyotes in Utah and Wyoming, and in Idaho, a nonprofit covers costs for hunters and trappers who successfully harvest wolves. (Peacher, 2020)

In 1921, Jane Marguerite Lindsley notably cracked open the door to the National Park Service’s (NPS) acceptance of women in the workforce when she was one of three women to be appointed as a part-time seasonal park ranger by Yellowstone Park Superintendent Horace

Albright. In doing so, Albright notably “diverged from the norm of only hiring men and hired eight to 10 women rangers, including Lindsley, during his tenure.” (“Explore the trail,” n.d.) Four years later, Lindsley proved her mettle further by becoming the NPS’s first permanent, full-time female ranger.

Author Megan Kate Nelson brings a serious historical pedigree to her latest book, Saving Yellowstone: Exploration and preservation in reconstruction America. After all, this is someone who already has two books under her belt – Ruin nation: Destruction and the American Civil War and The three-cornered war: The union, the confederacy, and native peoples in the fight for the west – as well as a regular column for Civil War Monitor that burrow deeply into a harrowing and seismic period of American history.

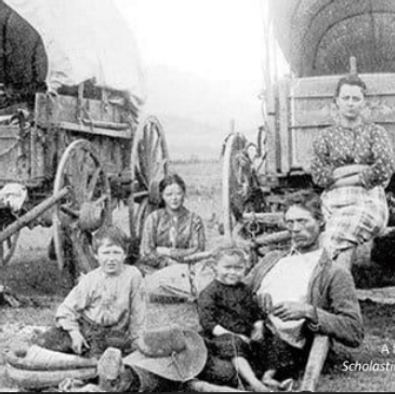

There’s no story behind the Oregon National Historic Trail without the story of those who created the 2,170-mile pathway across the West in the early 19th century. Between 1840 and 1880, more than 400,000 people traveled from the jumping-off point of Independence, Missouri, to the Willamette Valley in Oregon (though there were variations in starting points, and some

settlers veered south to California and took various routes overland as the years wore on). Their wagon wheels carved a route that would continue to be followed by generations seeking a better life until the railway system made such a grueling transcontinental trip no longer necessary.

Ever since Europeans first set foot on this continent, they have plundered the possessions of the many indigenous tribes that were already here. They did not merely appropriate gold jewelry and fine pottery; they also took human remains and other items associated with funeral

ceremonies. Though uncommon, when non-Native Americans felt the need to justify their actions, they claimed they sought “a representative collection of what anthropologists thought were disappearing cultures.” (Hawkins, 2021)